Commons history

The Commons weave a rich thread through the history of Tunbridge Wells and Rusthall, from Stone Age hunter-gatherers to Saxon swineherds and medieval lords of the manor. It is fascinating to read how the inhabitants of the past created the beautiful Commons that we all know and love today.

-

The history of Tunbridge Wells & Rusthall Commons

-

Mesolithic hunter-gatherers dwelling amidst the rocks

The earliest known inhabitants of the Commons were the [Mesolithic] hunter-gatherers of about 4500 BC who led a nomadic lifestyle and regularly used the rock outcrops in the area to camp.

The rocks were very visible in the vast Wealden forest, and the overhangs of the sandstone cliffs provided shelter and protection. These early inhabitants probably encouraged the development of heathland in the vicinity by burning to create open areas that would attract grazing deer. Flint implements used at this time have been found on Rusthall Common, near the rocks at Happy Valley and Denny Bottom.

To find out more about the archaeological site in Rusthall read Nigel Stapple’s blog

-

Saxon times (400-1066) – Rustwell and early settlements

The Commons first appeared in recorded history in Saxon times. The earliest mention of ‘Rusthall’ occurs in a charter of 765AD, in which King Egbert of Kent granted to Diora, bishop of Rochester, property at Halling (located near the Medway, south of Rochester) along with its associated swine pastures, including those located at Speldhurst and Rustwell. (Rustwell is thought to refer to the chalybeate – iron-containing – springs in the area, particularly the colour of their water.)

Swine pastures, known as ‘dens’, were carved out of the Wealden forest in considerable numbers from the 5th century onwards. Bishop’s Down, the ancient name of Tunbridge Wells Common may originally have been ‘Bishop’s Den’. The dens were used in autumn to fatten pigs for slaughter by feeding them on acorns and ‘beech mast’ (beechnuts).

Swine pastures, known as ‘dens’, were carved out of the Wealden forest in considerable numbers from the 5th century onwards. Bishop’s Down, the ancient name of Tunbridge Wells Common may originally have been ‘Bishop’s Den’. The dens were used in autumn to fatten pigs for slaughter by feeding them on acorns and ‘beech mast’ (beechnuts). Over the years these pastures began to attract a permanent population, and many developed into the Wealden towns and villages of today. While there was some settlement at Rusthall it never grew into anything large enough to be labelled a village. Until the development of Tunbridge Wells as a spa resort, it remained no more than a scattering of dwellings in an outlying corner of Speldhurst parish.

Over the years these pastures began to attract a permanent population, and many developed into the Wealden towns and villages of today. While there was some settlement at Rusthall it never grew into anything large enough to be labelled a village. Until the development of Tunbridge Wells as a spa resort, it remained no more than a scattering of dwellings in an outlying corner of Speldhurst parish. -

Later medieval times (1066-1599)

Before the development of the Pantiles in the late 17th century, the Tunbridge Wells Common adjoined the heathland of Waterdown Forest to the south (which itself extended as far as Wadhurst, East Sussex). With settlement came extensive clearance of trees and the spread of heathland over a wide area. The landscape for the future town was described in 1656 as “a valley compassed about with stony hills, so barren, that there groweth nothing but heath upon the same.”1 The same source refers to the wells as ‘Queen Mary’s Wells’, as Tudor queen Mary I had visited them.

The emergence of Rusthall Manor

Rusthall became a manor2 in the mediaeval period, with a lord, freeholders, and ‘wastes’. The land was originally part of the larger Wrotham Manor. The freeholders, or freehold tenants, were inhabitants who had been permanently granted portions of land within the manor boundaries by the lord, while being required to pay certain feudal dues. The ‘wastes’ of the manor, which we know today as the two Commons, were available to the freeholders for grazing their animals, and as sources of what was later described as “marl, stone, sand, loam, mould, gravel or clay”, as well as “gorse or litter (straw)”.

Rusthall became a manor2 in the mediaeval period, with a lord, freeholders, and ‘wastes’. The land was originally part of the larger Wrotham Manor. The freeholders, or freehold tenants, were inhabitants who had been permanently granted portions of land within the manor boundaries by the lord, while being required to pay certain feudal dues. The ‘wastes’ of the manor, which we know today as the two Commons, were available to the freeholders for grazing their animals, and as sources of what was later described as “marl, stone, sand, loam, mould, gravel or clay”, as well as “gorse or litter (straw)”.1 The Queen’s Well: That is, a Treatise of the Nature and Virtues of Tunbridge Water, by Lodowick Rowzee (Belgium born), Doctor of Physick, Ashford Kent, printed for Robert Boulter, at the Turk’s Head, Bishopsgate Street, 1670. Included (from page 328) in The Harleian Miscellany: A Collection of Scarce, Curious, and Entertaining Pamphlets and Tracts, selected from the library of Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford, Volume 8, edited by William Oldys and Thomas Park, 1811.

2 Land granted by a king to someone in return for that person providing military support when needed by the king.

-

Early modern times (1600-1837) – the springs

In 1606 Dudley Lord North, while in poor health, was staying at Eridge Castle, Eridge Park, with Lord Abergavenny, whose estate shared a border with the Manor of Rusthall. While riding along what is now known as Eridge Road, he spotted some orange-coloured water on the edge of the Common that he recognised as coming from a chalybeate (iron-bearing) spring, similar to those found at Spa in Belgium, which were already famous for their supposed health-giving properties.

In 1606 Dudley Lord North, while in poor health, was staying at Eridge Castle, Eridge Park, with Lord Abergavenny, whose estate shared a border with the Manor of Rusthall. While riding along what is now known as Eridge Road, he spotted some orange-coloured water on the edge of the Common that he recognised as coming from a chalybeate (iron-bearing) spring, similar to those found at Spa in Belgium, which were already famous for their supposed health-giving properties.Subsequently, Lord North began to regularly drink the spring water, claiming that it restored him to perfect health. News of it spread rapidly, and in 1608 Lord Abergavenny obtained permission from the Lord of the Manor to sink the first well on the site for the convenience of visitors.

Charles Strange’s observations

According to Charles Hilbert Strange (born in Tunbridge Wells in 1867, died 1952) in his 1946 ‘The History of Tunbridge Wells’, “The place [in the 17th century] consisted of small clusters of dwellings, with nothing to link them together but the common participation of their occupants in the artificial life of society leaders playing at rusticity, and that bat for a few months in summer. Indeed, it was not until the nineteenth century was well started that the inhabitants lived here all the year round.”

Charles Strange also noted, “… in 1630, when Henrietta Maria consort of Charles I came on a six weeks’ visit, she resided with her suite in tents pitched upon the Common. Again, when Charles II and Queen Catherine (of Braganza) stopped here in 1663 although they occupied a house on Mount Ephraim which had been built by Sir Edmund King (1630-1709), his Majesty’s physician, the Royal retinue had to be accommodated in tents.” The house built by Sir Edmund is likely to have been Earl’s Court (now Molyneux Place). King James II of England (from 1685 to 1688) is said to have visited in 1670, and then his daughter Anne in the 1680s, who was subsequently Queen of England between 1702 and 1714.

Lord Muskerry

Having acquired the Manor of Rusthall in about 1660, Lord Muskerry (Charles MacCarty, 1st Viscount Muskerry); whose wife Margaret inherited Somerhill and South Frith – Southborough, Tunbridge Wells) improved access to the spring by building a new enclosure with an ornamental arch in 1664. His widow, Margaret, subsequently sold the Manor to Thomas Neale in 1682, who negotiated an agreement with the Freeholders allowing him to build shops, lodgings and other facilities for visitors on the southern edge of the Tunbridge Wells Common, adjacent to the spring. After a fire in 1687, he constructed the colonnade now known as the Pantiles. The Freeholders received an annual payment in compensation for loss of grazing rights.

The Rusthall Manor Act of 1739

In 1732, by which time the Manor had changed hands twice, a legal battle broke out between the new Lord of the Manor, Maurice Conyers (an Irish gentleman with the alternative name of O’Connor), and the Freeholders, over the question of continued compensation after Neale’s 1682 agreement had expired. The Freeholders were successful in maintaining their rights over the Pantiles site, and the resulting settlement was embodied in the Rusthall Manor Act of 1739.

In 1758 Conyers’ son John sold the estate to George Kelley (later a Sir), whose descendants held it until it was sold to the commercial concern Targetfollow in 2008. Kelley, who lived in Tunbridge Wells from the 1740s, was a medical doctor who became Sheriff of Kent in 1762. The house which he built on the edge of Tunbridge Wells Common in 1765 still survives, in enlarged form, as the Spa Hotel.

Early encroachments

Although the 1739 Act was primarily concerned with dividing rights over the Pantiles between the Lord and the Freeholders, it also required mutual consent of the two parties for any further encroachment (intrusion, such as building or enclosure) on the Commons. It thus provided a solid legal foundation for the survival of the Commons as an open space to the present day.

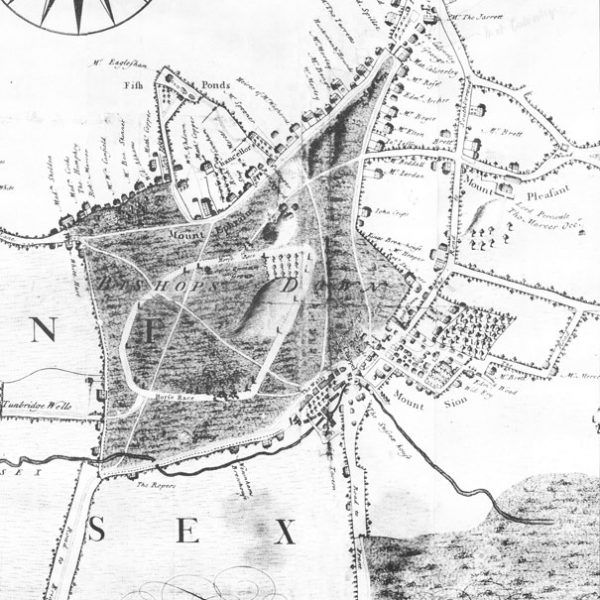

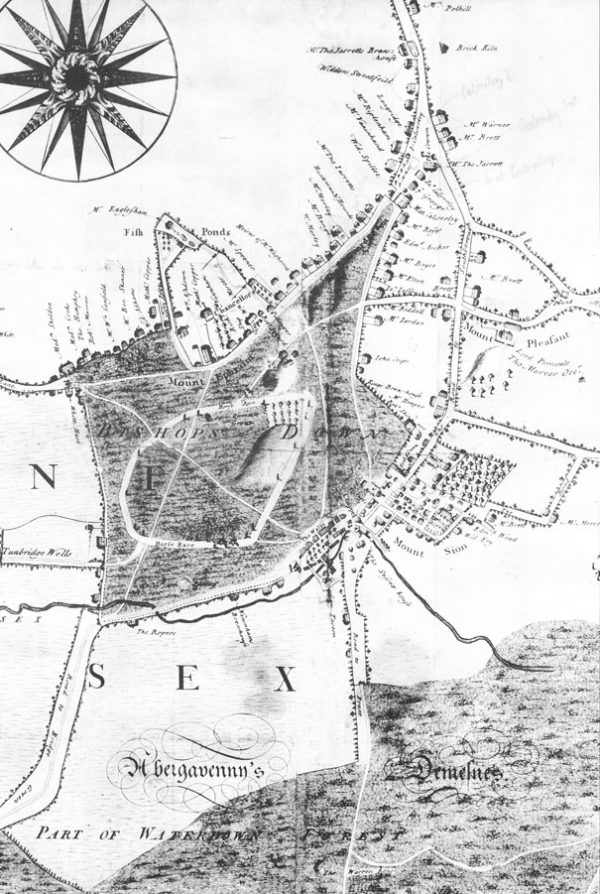

Although the 1739 Act was primarily concerned with dividing rights over the Pantiles between the Lord and the Freeholders, it also required mutual consent of the two parties for any further encroachment (intrusion, such as building or enclosure) on the Commons. It thus provided a solid legal foundation for the survival of the Commons as an open space to the present day.In earlier times, manorial courts had attempted to control the problem of unauthorised building on the Commons, but with limited success. Working buildings, as opposed to dwellings, were given retrospective permission in some instances. In other cases, fines were imposed on offenders, but the buildings remained in place. John Bowra’s map of ‘Bishops Down’ and Pantiles of 1738, produced in connection with the Rusthall Manor Act, shows several encroachments on Tunbridge Wells Common that had become established by then. There were two forges overlooking London Road, two lodging houses and a cottage on Mount Edgcumbe, and some buildings on the triangular portion of the Common where London Road and Mount Ephraim met. The latter probably began as workmen’s sheds, associated with quarrying stone and sand from the rock outcrops on the site, and gradually evolved into permanent dwellings.

Samuel Cripps’ observations

In 1779, in a letter to Fanny Burney, Samuel Cripps reports: “Tunbridge Wells is a place that to me appeared very singular. The country is all rock, and every part of it is either up or down hill … the houses, too, are scattered about it in a strange, wild manner, as if they had been dropped by accident, for they form neither streets nor squares.” (Quoted by Charles Strange’s in his ‘The History of Tunbridge Wells’.)

Fashionable holiday resort

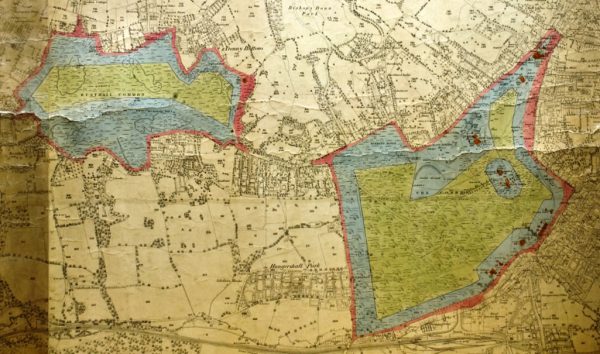

As Tunbridge Wells developed as a fashionable holiday resort, the Commons became more than a functional landscape – they provided a picturesque backdrop to the amusements that were provided for the benefit of visitors. The original Assembly Room for public entertainments was established in 1655 on Rusthall Common, with an adjacent bowling green. Although these facilities were moved to Mount Ephraim a decade later, Rusthall remained of enough importance for a Cold Bath (which can be located in the lower left of this old 1838 map of the Commons) and associated pleasure grounds to be opened in 1708, in the area later known as Happy Valley.

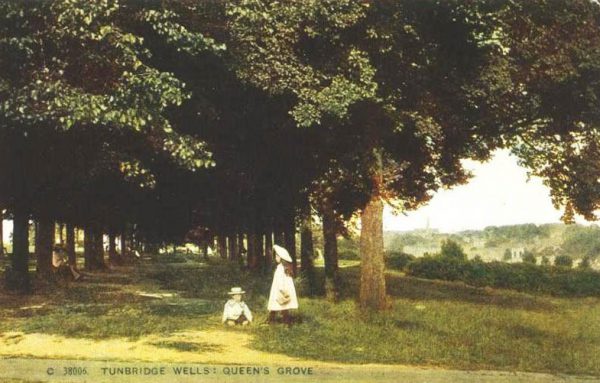

As Tunbridge Wells developed as a fashionable holiday resort, the Commons became more than a functional landscape – they provided a picturesque backdrop to the amusements that were provided for the benefit of visitors. The original Assembly Room for public entertainments was established in 1655 on Rusthall Common, with an adjacent bowling green. Although these facilities were moved to Mount Ephraim a decade later, Rusthall remained of enough importance for a Cold Bath (which can be located in the lower left of this old 1838 map of the Commons) and associated pleasure grounds to be opened in 1708, in the area later known as Happy Valley. Some eighteenth-century residents and visitors believed that the Commons would benefit from tree planting and other embellishments, but the planting of Queen’s Anne’s Grove in 1702 (along with the Queen Anne’s Oak a couple of years earlier) is the only reported example prior to 1835. Charles Strange reports that “the best part of three very wet days were occupied in the planting: a list is preserved of the names of those taking part, including 25 boys of Chapel School (now King Charles’).”

Some eighteenth-century residents and visitors believed that the Commons would benefit from tree planting and other embellishments, but the planting of Queen’s Anne’s Grove in 1702 (along with the Queen Anne’s Oak a couple of years earlier) is the only reported example prior to 1835. Charles Strange reports that “the best part of three very wet days were occupied in the planting: a list is preserved of the names of those taking part, including 25 boys of Chapel School (now King Charles’).”The Commons racecourse

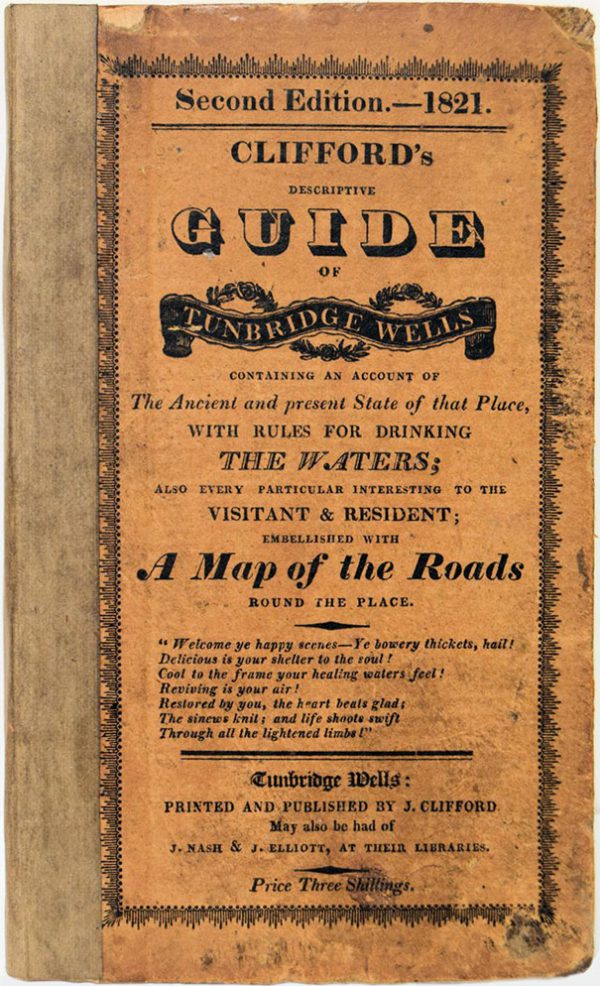

A racecourse was created on Tunbridge Wells Common from an early date in the 18th century (see Bowra’s map of 1738), and in 1801 the popular pastime of donkey riding was introduced. Clifford’s Tunbridge Wells guide (of 1818) reports that “The Common, on which are walks, rides, romantic rocks, the race ground, etc. has become a favourite place of resort with the visitors to the Wells. The turf is covered, during the summer, with flocks of sheep; and pedestrians, equestrians, and ‘asinurians’ (donkey riders), of all ranks, sexes and ages amuse themselves on it”. In a subsequent edition (1823) he encouraged his readers to explore Rusthall Common, where “the views over various parts of Kent and Sussex are the most delightful and extensive” and the rocks are “very remarkable for the singular shapes which many of them present”.

A racecourse was created on Tunbridge Wells Common from an early date in the 18th century (see Bowra’s map of 1738), and in 1801 the popular pastime of donkey riding was introduced. Clifford’s Tunbridge Wells guide (of 1818) reports that “The Common, on which are walks, rides, romantic rocks, the race ground, etc. has become a favourite place of resort with the visitors to the Wells. The turf is covered, during the summer, with flocks of sheep; and pedestrians, equestrians, and ‘asinurians’ (donkey riders), of all ranks, sexes and ages amuse themselves on it”. In a subsequent edition (1823) he encouraged his readers to explore Rusthall Common, where “the views over various parts of Kent and Sussex are the most delightful and extensive” and the rocks are “very remarkable for the singular shapes which many of them present”.Challenges for the Freeholders

By the beginning of the 19th century, the management of the Commons was in the hands of the Freeholders, who were responsible for regulating the use of the Commons for grazing and other purposes, collecting rents for permitted encroachments, and general management, such as maintaining ponds and drainage channels.

The growing population of the town put increasing pressure on the Commons, and the Freeholders began to realise that some active policing was necessary in order to “check the many trespasses and depredations that are constantly committed”. As well as the old problems of unauthorised encroachment, they now had to contend with the dumping of rubbish, burning of the gorse, extensive destruction of the soil by persons digging for marl and sand, and over-grazing. It was discovered that local residents were acquiring tiny pieces of land in the manor so that they could claim the right to pasture large numbers of animals on the Commons, greatly outnumbering those of the legitimate Freeholders. In 1824 the Freeholders formed a Committee to act as an executive between their annual meetings, and from 1827 they began to employ a ‘common driver’ and ‘pound keeper’ (responsible for the feeding and care of stray livestock) to oversee the Commons on a day-to-day basis.

-

The Victorian years

The Hogpounders

By the time John Colbran published his New Guide for Tunbridge Wells in 1839, the new Freeholder regime had improved their control of the Commons, executing “very summary justice on those who attempt to invade their rights”. It is Colbran who tells us how the Freeholders, on account of their enthusiastic tackling of abuses, had acquired the nickname of ‘hogpounders’, a term which “although originally applied in derision, is now rather courted than rejected by them”. This name alluded to the seizure of offending animals, which were not returned to the owner until a fine had been paid. At their annual meeting the Freeholders used to tour the manor, inspecting any unauthorised buildings or fences, after which they held a dinner known as the ‘Hogpounders Feast’.

Colbran, one of the Freeholders, was keen to remind his readers of their public-spirited attitude, describing the ‘hogpounders’ as “a body of men to whom the visitors and inhabitants of the Wells are greatly indebted, inasmuch as they are the means of protecting the beautiful Commons”.

The first deliberate attempts to beautify the Commons (since the 1700-1702 plantings) took place in this period, beginning with the planting of the Royal Victoria Grove in 1835, to commemorate the visits of the young Princess Victoria (who had greatly enjoyed her rides on the Common on her donkey called ‘Flower’), and to supersede the dying Queen Anne’s Grove.

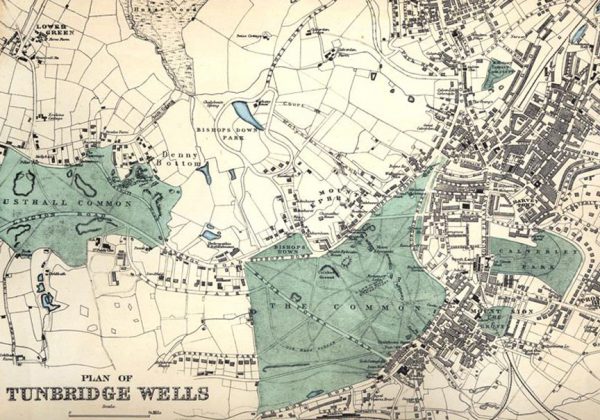

The Commons, their walks and vistas

The attraction of the area had changed by the mid 19th century. According to Granville, writing in about 1840, “… if Tunbridge Wells be crowded … it is not with people who come on account of the chalybeate … it is … the beauty of that cannot be subject to the caprice of fashion … which brings down the thousands from the metropolis anxious to enjoy the smiling neighbourhood of Tunbridge Wells, and inhale the bracing and pure breezes from the crests of the holy mounts, be they Ephraim or Sion. No watering places except Cheltenham has so many detached villas … grouped over the most diversified area of plains and hills of undulating ground that can be imagined, or arranged around a Common intersected by roads and ways, and fifty winding paths, that have all some important object at their termination; and most of them interspersed with insulated groups of trees, groves, and grotesque masses of rocks peeping above the surface in their grey nakedness. … When … you step onto the Common … by the Castle-road straight across that common … or by the more tortuous one called the London-road, you ascend imperceptibly towards the north to reach the highest point … you behold equally to the right and to the left a range of detached buildings more or less imposing, grand, or convenient, but all of them cheering and joyous …”

The attraction of the area had changed by the mid 19th century. According to Granville, writing in about 1840, “… if Tunbridge Wells be crowded … it is not with people who come on account of the chalybeate … it is … the beauty of that cannot be subject to the caprice of fashion … which brings down the thousands from the metropolis anxious to enjoy the smiling neighbourhood of Tunbridge Wells, and inhale the bracing and pure breezes from the crests of the holy mounts, be they Ephraim or Sion. No watering places except Cheltenham has so many detached villas … grouped over the most diversified area of plains and hills of undulating ground that can be imagined, or arranged around a Common intersected by roads and ways, and fifty winding paths, that have all some important object at their termination; and most of them interspersed with insulated groups of trees, groves, and grotesque masses of rocks peeping above the surface in their grey nakedness. … When … you step onto the Common … by the Castle-road straight across that common … or by the more tortuous one called the London-road, you ascend imperceptibly towards the north to reach the highest point … you behold equally to the right and to the left a range of detached buildings more or less imposing, grand, or convenient, but all of them cheering and joyous …”The Rusthall Manor Act of 1863

In 1861 the Freeholders decided that their role as guardians of the Commons required legal backing. With the support of the Manor they sought a new act of Parliament to supplement the Rusthall Manor Act of 1739. The result of their efforts was the Rusthall Manor Act of 1863, which established a formal register of Freeholders and empowered the Freeholders’ Committee to make byelaws.

The intent of the Freeholders was not entirely selfless. While protecting their own grazing and other rights, many of them were tradesmen and lodging-house keepers and so had an interest in maintaining the Commons as an attraction for visitors.

Brighton Lake and more

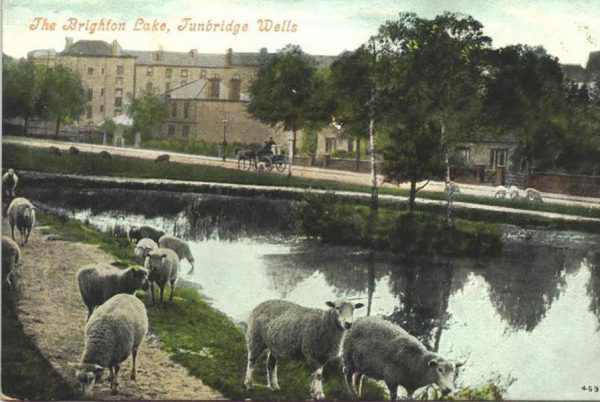

In 1858 representatives of the Freeholders met with the Poor Fund Committee, which was set up by Reverend William Law Pope to provide work for unemployed labourers. They agreed a programme of works that included the creation of what is now known as Brighton Lake, from a swampy hollow, and the levelling of a “greensward terrace walk” running parallel with Eridge Road, on the slope above the new lake.

In 1858 representatives of the Freeholders met with the Poor Fund Committee, which was set up by Reverend William Law Pope to provide work for unemployed labourers. They agreed a programme of works that included the creation of what is now known as Brighton Lake, from a swampy hollow, and the levelling of a “greensward terrace walk” running parallel with Eridge Road, on the slope above the new lake.In 1867 the Freeholders agreed to collaborate with the Tradesmen’s Association in planting trees on various parts of Tunbridge Wells Common, whose open heathy landscape appeared to many, to be somewhat barren. The newly formed Association for Promoting the Interests of the Town of Tunbridge Wells approached the Freeholders in 1874 with a scheme to create a turf walk or promenade on the top of the Common along Mount Ephraim. This was finally put into effect in 1881, providing a pleasant stroll for fashionable visitors, from which they could obtain panoramic views of the town.

Late 19th century controversy

The last decade, of the 19th century, of the Freeholders’ supremacy over the Commons was marked by controversy. This had its beginnings in 1882 with claims on the part of the Local Board (the town’s then local-government body) and other prominent townsfolk that the Freeholders were becoming too lax in preventing encroachments. There had long been a practice of permitting the occupiers of property on or adjacent to the Commons to take over small portions of land on payment of an annual rent, but now there were requests for larger enclosures; the dwellings situated on the Commons originally only owned the land on which their footprints stood. This had not been a problem with workmen’s cottages, but when they were rebuilt as desirable Victorian residences, the owners became unhappy that the general public were able to walk right up to their property and peer through their windows.

St Helena Cottage encroachment

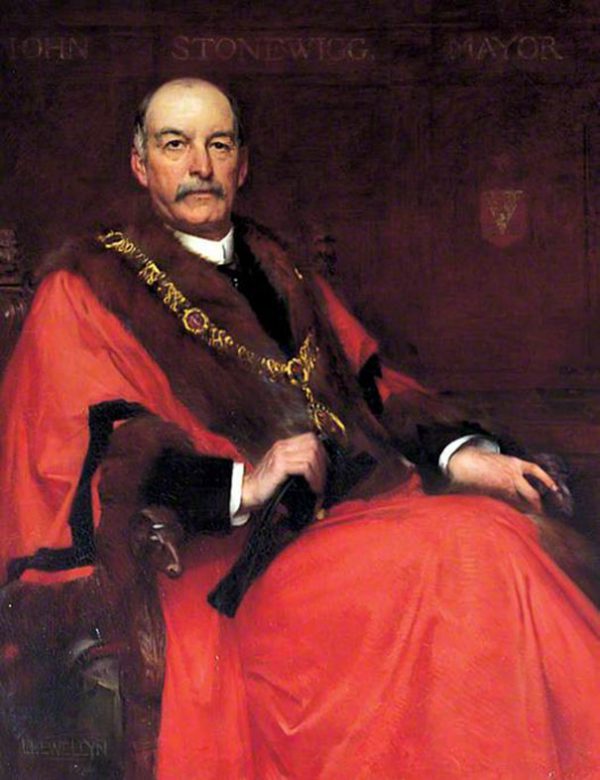

The most heavily criticised incident occurred when the Freeholders’ Committee gave permission to the owner of St Helena Cottage, situated at the eastern end of Tunbridge Wells Common, to “enclose a portion of the rocks and Common with an iron fence”. The Local Board protested that “the recent enclosures and obstructions were illegal”, while local solicitor Frank William Stone (later Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, 1898-1900), along with his brother Frederick, launched a personal campaign to change the Freeholders’ policy. The brothers owned land within the Manor boundary and so were entitled to register as Freeholders. Gathering together sixteen eligible supporters (including the Tunbridge-ware maker Thomas Barton), they submitted their names to the Freeholders’ Committee in October 1882. Initially there was resistance, the meeting resolving that “the claims of the above … have not been made out to the satisfaction of the Committee”. Several of the campaigners appeared at the Annual Meeting of the Freeholders a month later but were ejected.

The most heavily criticised incident occurred when the Freeholders’ Committee gave permission to the owner of St Helena Cottage, situated at the eastern end of Tunbridge Wells Common, to “enclose a portion of the rocks and Common with an iron fence”. The Local Board protested that “the recent enclosures and obstructions were illegal”, while local solicitor Frank William Stone (later Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, 1898-1900), along with his brother Frederick, launched a personal campaign to change the Freeholders’ policy. The brothers owned land within the Manor boundary and so were entitled to register as Freeholders. Gathering together sixteen eligible supporters (including the Tunbridge-ware maker Thomas Barton), they submitted their names to the Freeholders’ Committee in October 1882. Initially there was resistance, the meeting resolving that “the claims of the above … have not been made out to the satisfaction of the Committee”. Several of the campaigners appeared at the Annual Meeting of the Freeholders a month later but were ejected.A new Freeholders’ Committee

By the time of their meeting in February 1883, the Freeholders’ Committee had been forced to concede that there was no legal reason to exclude the eighteen new applicants, and they were registered without further argument. In May a further list of twenty names was submitted and accepted, including prominent members of the Local Board. The newcomers now had a clear majority over their opponents, and the stage was set for a takeover of the Freeholders’ Committee.

By the time of their meeting in February 1883, the Freeholders’ Committee had been forced to concede that there was no legal reason to exclude the eighteen new applicants, and they were registered without further argument. In May a further list of twenty names was submitted and accepted, including prominent members of the Local Board. The newcomers now had a clear majority over their opponents, and the stage was set for a takeover of the Freeholders’ Committee.The Freeholders’ Annual Meeting in November 1883 was a stormy affair at which the chairman, John Stone Wigg (later the town’s first mayor), had considerable difficulty keeping order. Frank Stone’s supporters arrived in force and succeeded in electing an entirely new Committee from among their number. The vote was greeted by shouts of protest from their opposition, who tried to argue that it was technically invalid, but the chairman overruled them. A vote was also carried to the effect that “all obstructions, posts and rails, and chain fencing between Onslow House and Romanoff Lodge and Mount Edgcumbe House be forthwith removed”.

The Lower Cricket Ground

In later years Frank Stone was credited with “saving the Commons”, which was doubtless an exaggeration, but the election of the new Committee did mark a return to the stricter policy of earlier times. However, positive developments were not ruled out. In 1885-1886 the Lower Cricket Ground was levelled to relieve pressure on the older (Upper) ground on Tunbridge Wells Common, and Rusthall Common was provided with a formal cricket ground for the first time. The Lower Cricket Ground had earlier been used informally as a playing field by the boys of Romanoff House School in London Road, and it was also the site of the annual bonfire on November 5th, which the Freeholders had permitted since 1860 in an effort to eliminate the traditional custom of indiscriminate burning of gorse bushes. In 1886 a scheme was brought forward to purchase the old forge and associated buildings at Fonthill, to demolish them, and to return the land to the open Common, but due to the change of administration four years later the project was never brought to completion.

In later years Frank Stone was credited with “saving the Commons”, which was doubtless an exaggeration, but the election of the new Committee did mark a return to the stricter policy of earlier times. However, positive developments were not ruled out. In 1885-1886 the Lower Cricket Ground was levelled to relieve pressure on the older (Upper) ground on Tunbridge Wells Common, and Rusthall Common was provided with a formal cricket ground for the first time. The Lower Cricket Ground had earlier been used informally as a playing field by the boys of Romanoff House School in London Road, and it was also the site of the annual bonfire on November 5th, which the Freeholders had permitted since 1860 in an effort to eliminate the traditional custom of indiscriminate burning of gorse bushes. In 1886 a scheme was brought forward to purchase the old forge and associated buildings at Fonthill, to demolish them, and to return the land to the open Common, but due to the change of administration four years later the project was never brought to completion.Tunbridge Wells Improvement Act of 1890

The history of the Act, and particularly the part relating to the Commons, is complex. The parliamentary process was originally set in motion by the old Local Board, one of whose prime objectives was to gain as much control as they could over the management of the Commons, having been frustrated by their impotence in the matter of the enclosure of St Helena. The Manor and Freeholders, who felt strongly that they had managed the Commons perfectly satisfactorily since time immemorial, objected to the Board’s ambitions and petitioned Parliament in opposition to the original version of the Bill. Negotiations were opened between the three parties, and eventually a compromise was reached establishing that the Conservators should consist of twelve persons, four persons each appointed by the Manor, by the Freeholders, and by the Council, with the duty to “maintain the Commons free from all encroachments”. Accompanying the Act was the first definitive map of the boundaries of the Commons, with its then-permitted encroachments.

The history of the Act, and particularly the part relating to the Commons, is complex. The parliamentary process was originally set in motion by the old Local Board, one of whose prime objectives was to gain as much control as they could over the management of the Commons, having been frustrated by their impotence in the matter of the enclosure of St Helena. The Manor and Freeholders, who felt strongly that they had managed the Commons perfectly satisfactorily since time immemorial, objected to the Board’s ambitions and petitioned Parliament in opposition to the original version of the Bill. Negotiations were opened between the three parties, and eventually a compromise was reached establishing that the Conservators should consist of twelve persons, four persons each appointed by the Manor, by the Freeholders, and by the Council, with the duty to “maintain the Commons free from all encroachments”. Accompanying the Act was the first definitive map of the boundaries of the Commons, with its then-permitted encroachments.Management responsibility goes to the Conservators

The present system of managing the Commons, under a body of twelve Conservators, was established by the Tunbridge Wells Improvement Act of 1890 (a copy of which can be downloaded), which set down the powers and responsibilities of the new Borough Council established in the previous year, and which contained a thirteen-page section on the Commons.

The Conservators took over the day-to-day management of the Commons, as well as the power to formulate byelaws, from the Freeholders’ Committee. The Act also stated explicitly that “the inhabitants of Tunbridge Wells and the neighbourhood shall have free access”. Although the 1890 Act is no longer in operation, its essential provisions relating to the Commons were re-enacted in the County of Kent Act of 1981, a copy of which can be downloaded.

The Commons at their best

In the late Victorian and Edwardian period (about 1890 to 1910), the Commons were probably to be seen at their best. They were much frequented by residents and visitors, as can be seen from the numerous postcard views such ‘Sunday Afternoon on the Common’, which depicts crowds sitting on the grassy slopes overlooking London Road. The old problems of digging and quarrying that made parts of the Commons unsightly, and excessive numbers of grazing animals, had now come to an end.

As belief in the value of the Pantiles chalybeate spring declined, so the town’s claim to be a health resort shifted to the local environment in general, with walks on the breezy Commons being highly recommended to promote recovery from sickness. According to the 1903 town guide, “On the hottest day in summer there is always a cool, scent laden breeze, sweeping over the glorious Common, and to breathe this air is to take in new life and enjoy a feeling of stimulated vitality and buoyancy such as only a pure and salubrious atmosphere and pleasant surroundings can arouse.”

The Commons’ natural and wild condition

At the same time, the natural vegetation of the Commons began to be appreciated by the public in general as well as by the dedicated botanist. Pelton’s Illustrated Guide to Tunbridge Wells, constantly reprinted from 1871 to the beginning of the new century, contains a characteristic description: “To our modern taste its natural and wild condition renders it far more attractive than the artificial parks which it is the fashion to provide for the healthful recreation of the dwellers in large cities. The furze bushes and the brake are the most noticeable ornaments; but the whole expanse abounds with other plants and blossoms — ling and heath, chamomile and thyme, milkwort and wild violets, being among the most abundant. In April and May, the golden bloom of the furze, which is unusually profuse in this spot, delights the eye, and its rich perfume scents the breeze.”

Tree planting and self-seeding

The practise of largescale tree planting, begun under the management of the Freeholders, was continued by the Conservators. The general view was that additional trees served to enhance the natural beauties of the Commons. In 1895 the Tradesmen’s Association, who with their interest in promoting tourism maintained a keen interest in the Commons, organised a scheme whereby individuals and organisations could contribute one or more trees, and about 150 were planted over the course of a week in November. The new and outgoing mayors, Major Fletcher Lutwidge (1895-1898) and Sir David Salomons (1894-1895) ceremonially performed the first plantings beside Major York’s Road in 1895. What was not anticipated was that as these trees matured and grazing declined, they would seed themselves all over the Commons, beginning a process of uncontrolled transformation of heathland to woodland.

3 p618- of The Spas of England and principal sea-bathing places, by Augustus Bozzi Granville (1783-1872), Henry Colborn, Gt Marlborough Street, London, 1841.

-

The early 1900s

Loss of open views

In 1931, Charles Hilbert Strange gave a lecture to the Tunbridge Wells Natural History Society, in which he related the history of commemorative tree planting on the Commons, including the most recent examples (near Highbury and leading up to Rusthall Church) to mark the accession and coronation of George V. But he concluded by warning that the number of trees was becoming excessive, saying, “If there is to be any further tree-planting on the Common, it is hoped that it will be done with circumspection and foresight. I am inclined to think we have almost enough forest trees. It is a fact that the view from Mount Ephraim, an ever-lovely panorama of moorland, field and forest, is becoming more and more intercepted by growing trees. Above all, we ought to aim at a better care and cultivation of the trees we already possess; that they may be protected from injury, cut down and replaced where decayed, and those that are neither useful for shade nor ornamental to look at should be removed.”

However, further commemorative planting did take place in 1935, to celebrate George V’s Silver Jubilee, and on a larger scale for the coronation of George VI in 1937. In the latter year, King’s Avenue with its flowering cherries was created along the Donkey Drive (Mount Edgcumbe Road), along with King’s Grove south of Mount Edgcumbe (later swamped by invading scrub).

Disappearing heathland – decline of grazing

Meanwhile, the Chamber of Trade (incorporating the old Tradesmen’s Association) had also noticed that all was not well on the Commons. In a report presented to the Conservators in the same year as Charles Strange’s lecture (1931), they pointed out that an excessive number of young trees, mostly birches, were springing up, that ponds were silting up, and that the traditional heathland vegetation was diminishing. In subsequent years several prominent residents complained about problems such as the invasion of bracken and the fact that heather was “rapidly disappearing”.

No one seems to have realised that the immediate cause of these changes was the decline in grazing, which had ceased altogether by the outbreak of World War II. Wartime conditions then disrupted the management of the Commons, causing unavoidable neglect. Any effective action that the Conservators might otherwise have taken was prevented, not only by a shortage of manpower but also by various military and civil defence activities on the Commons themselves.

World War II bombing

As early as 1938, some of the town’s first air raid shelters appeared in the form of open trenches on Tunbridge Wells Common, while in October 1939 the Borough Council was authorised to convert the caves under St Helena Cottage into more permanent shelters.

By December 1940 there were already four bomb craters on the two Commons, including one in the middle of the Higher Cricket Ground. A young resident of Tunbridge Wells, Elizabeth Spicer recounts, “On the Common there were some high rocks and my sister and I and friends would often play around the rocks. One day a Messerschmitt came over and tried to machine gun us, but we were hiding under these rocks. No one was hurt and afterwards we all went home and behaved as though nothing had happened.”

World War II clearance and other incursions

In 1941 largescale clearance of gorse bushes and other vegetation was undertaken in order to avoid the risk of fires caused by incendiary bombs. Such fires, it was thought, would not only endanger houses on and around the Commons, but would also “serve as a beacon lighting up the town for a further enemy attack”.

In 1942 further works were carried out. A reinforced concrete shelter was constructed by Brighton Lake, and the National Fire Service constructed three steel tanks on concrete bases, two on Tunbridge Wells and one on Rusthall Common, each holding 23,000 gallons of water. In the same year, the railings around the two cricket grounds were removed for the war effort. By this time, several pieces of land on both Commons had been requisitioned by the military for purposes which included the siting of anti-aircraft guns and searchlight emplacements. The Conservators complained vigorously about the hazards caused by the widespread presence of entrenchments and other concealed excavations, especially when a local resident was injured by falling into an unprotected gun pit.

Post-war labour shortages

The military authorities paid compensation for the damage done to the Commons, and it was reported that almost all damage had been made good by 1946. However, general neglect led to uncontrolled growth of vegetation that did not prove so easy to reverse. The absence of sheep and cattle left the task of keeping back scrub and bracken to human labour, but this was in short supply. The desirability of reintroducing grazing was debated by the Conservators in the late 1940s, but clearly no way of achieving this could be found. In 1947, the occupant of the cottage at Bull’s Hollow complained to the Conservators that “seedlings had grown into trees and her premises were now enclosed in a tangle of bracken, trees and weeds”, only to be told that “owing to shortage of labour it had not been possible to effect the clearance of undergrowth”. In the following year, the Freehold Tenants made more general observations on “the present unsatisfactory state of the Commons” but received a similar answer.

-

Modern-Elizabethan period

Years of limited management

On the day of Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953, Tunbridge Wells Common fulfilled its traditional function as a place to congregate and celebrate. This was centred on the Upper Cricket Ground, where “a great crowd assembled for the fancy-dress parade, to hear the Queen’s message broadcast, to see a firework display and the bonfire lit, and to take part in community singing.” A ceremony took place with the Mayor and Deputy Mayor planting two flowering cherries near the cricket pavilion.

Meanwhile, the Conservators were fighting what seemed to be a losing battle against rampant saplings and bracken. In the mid 1950s they reported “sycamore and silver birch trees were becoming too prolific”, instructing the then-called Commons Surveyor “to report as to the action which may be taken to restrict the spread of bracken”. The fading memory of the Commons’ original condition made it increasingly difficult to formulate a coherent policy, or define a vision, for the kind of landscape wanted for the Commons.

Decades of inconsistent actions and growing tree population

In 1957, the Surveyor carried out a detailed survey of the Commons and made proposals for restoring them. However, these perpetuated the now largely woodland nature of the Commons and did not address the now-vanished heath and grassland. The results were inconsistent. Some saplings of unwanted species were eliminated, but at the same time 269 fresh saplings, mainly oak, were planted. The racecourse was cleared, and but despite significant debate about removal of undergrowth, it ended in no more than a “policy of clearing undergrowth and small defective trees alongside roads and footpaths”. The possibility of grazing by goats was considered, yet a policy of exterminating rabbits was pursued. No one it appeared to appreciate that rabbits helped to maintain open grassland.

During the 1960s, management of the Commons had become a ‘holding’ operation, simply to stabilise what was understood to be their natural condition. Radical intervention was no longer considered. This situation was typified by the Happy Valley viewing point, which had been under discussion throughout the decade. When it was first reported in 1961 that the view so much admired by the Victorians and Edwardians, was now invisible due to obscuring vegetation, the Surveyor ordered the removal of “dead and dying holly trees and relatively small and poorly shaped oak trees”. The same type of work was carried out in 1967, but by the following year residents of Rusthall were still complaining that the view was blocked. Two years later, similar arguments began over the condition of Toad Rock.

The Commons are no longer ‘open’

By the 1970s, the originally open character of the Commons had been almost entirely lost. Increasing numbers of self-sown trees, along with a spread of bracken and bramble, had produced a landscape that for the most part appeared to be woodland traversed by narrow footpaths. The Racecourse had become a forest ride. Heathland had been virtually extinguished, surviving only in a few dwindling patches which were being steadily encroached upon by taller undergrowth. The once-ubiquitous gorse bushes flourished only in a few open spots, while elsewhere they were being shaded out by the tree canopy. Acid grassland still survived on the northern and southern fringes of Tunbridge Wells Common, but it was clearly threatened by advancing woodland. Victorian seats hemmed in by vegetation hinted at lost viewing points. Some rock formations, notably at Mount Edgcumbe and Happy Valley, had been so densely engulfed by foliage that their existence was generally unknown. And the last of the little informal ponds had been reduced to boggy hollows, well on their way to complete disappearance.

Local perceptions about the appearance of the Commons

The process of loss on open land, so dramatic when set out in print, or when Victorian views of the Commons are compared with their modern equivalents, was rendered less noticeable by the gradual change. Older residents remembered what the Commons had looked like in earlier times, but over the years became accustomed to its new appearance. On the other hand, younger folk, and those recently moved into the area, naturally imagined that this was how the Commons were meant to be. Almost all shared a general perception that “nature looks after itself”, failing to realise that in England no landscape is entirely natural, but is the product of a conscious or unconscious collaboration between human activity and natural processes.

Great Storm of 1987, the first Management Plan and emergence of The Friends

The consequences of the Great Storm on the night of 15th October 1987 led many to look at the Commons in a fresh way. Local people awoke to discover that many trees which had appeared to be permanent features of the landscape had met a premature end. Although not as devastated as some areas, there was a considerable loss of trees on the Commons. Over this unsettling time, public interest in the Commons increased, resulting in the establishment of the Friends of Tunbridge Wells and Rusthall Commons in 1991.

The Conservators commissioned the Kent Trust for Nature Conservation to research the history of the Commons, conduct an environmental survey, and from these prepare a Management Plan to serve as a long-term roadmap for future management. The resulting Plan did not aim to put the clock back to 1900, which would be impossible without re-establishing grazing, but to establish a mosaic of diverse habitats, of which woodland would still form a part. It was formally adopted by the Conservators in 1992.

Recent History

Since 1992, considerable progress has been made in implementing the new management regime. Areas of scrub dominated by holly have been cleared and returned to wood pasture, heathland or rough grass. Surviving patches of heather and acid grassland have been encouraged to spread and their characteristic butterflies are appearing in new areas, assisted by the wider fringes of the footpaths and woodland tracks. Ponds have been brought back to life, providing homes for dragonflies, amphibians and other creatures. And lost rock formations at Mount Edgcumbe, Denny Bottom and Happy Valley have been exposed once more to view.

The original management plan has been updated twice, in 2005 and 2017. Much more remains to be done, but a fine start has been made to making the Commons as attractive to locals and visitors, and to their native plants and animals, as they were a century ago.

-

Mesolithic hunter-gatherers dwelling amidst the rocks

-

The Manor of Rusthall and the Freehold Tenants

The Manor of Rusthall

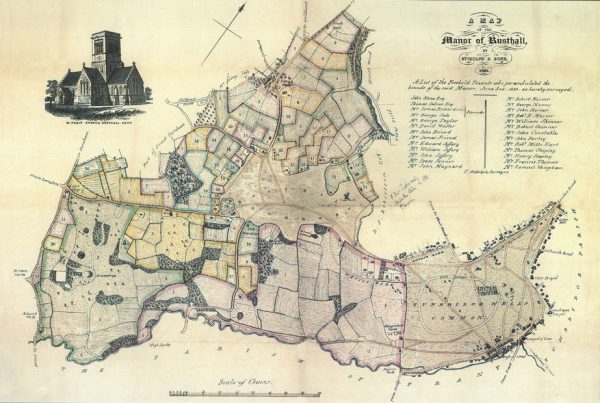

The Manor of Rusthall is an ancient feudal holding that extends from London Road in Tunbridge Wells westward to Langton Green, and from Eridge Road north towards Rusthall and Speldhurst. Tunbridge Wells and Rusthall Commons were ‘wastes’ of the Manor, which were left uncultivated and unenclosed.

The early history of the manor of Rusthall is obscure, since its population was not large enough to constitute a village and, until the development of Tunbridge Wells, it was simply an outlying part of Speldhurst parish. The first known holder of the manor, Hilary de Sutton, is mentioned in a document dating back to 1268. The location of the mediaeval manor house is unknown. Colbran’s town guide of 1839 suggests four possible sites near Bishops Down. From 1664 onward, successive Lords of the Manor were responsible for developing the Pantiles and spa.

The current Lord of the Manor is Targetfollow (Pantiles) Limited, having bought the Manor along with the freehold titles of the two Commons and most of the Pantiles in 2008. Targetfollow is a privately-owned commercial property company, based in Norwich.

The Freehold Tenants

The Freehold Tenants of the Manor of Rusthall were originally inhabitants who had been permanently granted land within the Manor by the Lord and were expected to pay feudal dues. These landholders had certain rights over the ‘wastes’ of the Manor, primarily the two Commons, for grazing their animals, and as sources of “marl, stone, sand, loam, mould, gravel or clay”, as well as “gorse or litter (straw)”.

Over time, as portions of the ‘wastes’ were developed, most notably around the Pantiles, the grazing and other rights of the Freehold Tenants were converted into an interest in income from the Commons which survives to the present day. The current Freehold Tenants use their share of the income to fund improvement projects on the Commons in support of the Conservators’ Management Plan.

Owners of land or property within the Manor of Rusthall are still entitled to register as Freehold Tenants. To qualify, proof of title must be confirmed by the Committee of the Freehold Tenants. Registration forms are available from the secretary of that Committee, Stephen Lacey, at sl@stephenlacey.co.uk .

The affairs of the Freehold Tenants and their role in managing the Commons are governed by various Acts of Parliament: the Rusthall Manor Acts of 1739, 1863 and 1902, the Tunbridge Wells Improvement Act of 1890 and the 1981 County of Kent Act.